- 2018-01-29

Slavery, Plagues, and Restoration

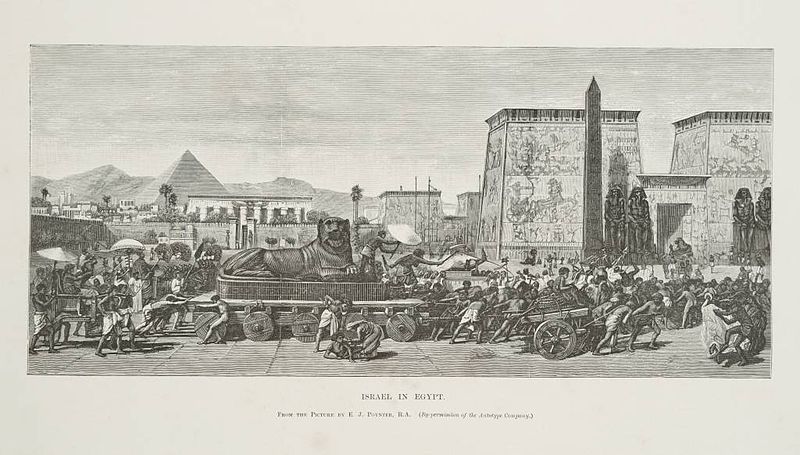

The timely message of Handel’s Israel in Egypt.

The Timely Message of Handel’s Israel in Egypt

By Thomas May

“I’m struck by how the Exodus story has spoken to so many different peoples over the last three millennia — especially today, with so many refugee crises and displaced peoples,” says Los Angeles Master Chorale’s Kiki and David Gindler Artistic Director, Grant Gershon. “To me, the heart of the Exodus story is this miraculous and unique restoration of a people to their homeland.”

If Messiah holds the rank of one of the most reliably evergreen fixtures of the musical calendar, year after year, Israel in Egypt — which shares some fascinating characteristics with Messiah — might almost seem to have been designed with the early 21st century and its diasporas in mind. Moreover, this evening’s performance juxtaposes Handel’s moving and richly inventive score with the unique art of Kevork Mourad, whose work passionately engages with contemporary crises — particularly the plight of the dispossessed in his native Syria.

Watch the Israel in Egypt preview

“Now, more than ever, it’s important to be able to join our voices together to show what is happening in the world,” Mourad says. “With this work, I hope to create a mirror that can help us realize that the time has come to build something after so much greed and destruction.” This collaboration continues the Master Chorale’s ongoing Hidden Handel project — launched two seasons ago with Alexander’s Feast — which aims to shed new light on some of Handel’s overlooked oratorio masterpieces through semi-staged, multimedia productions that feature contributions by cutting-edge artists.

HANDEL’S SELF-REINVENTION WITH ISRAEL IN EGYPT — In 1711, while still in his twenties, Handel scored his first hit in London with his opera Rinaldo. Its success prompted him to settle permanently in England, restyling himself from Georg Friedrich Händel to George Frideric Handel. A few years later, the boss he had left behind in Germany would likewise make the move and become — somewhat embarrassingly for the truant composer — Handel’s new sovereign (as King George I).

Handel favored a style of tragic opera (opera seria) that was based, for the most part, on mythological or historical figures, set to Italian librettos, and that showcased star singers. Yet by the late 1730s, dramatic changes in public taste were turning this into an unsustainable business model. Opera was always a risky business, but it precipitated financial catastrophe for Handel, and at the end of the 1737 season, he suffered what was likely a serious stroke, triggered in part by over-exertion.

But the composer was ripe for another reinvention. After a miraculously short recovery, Handel was back in action, and he began to turn his attention increasingly toward the English oratorio. Oratorio usually focused on subject matter drawn from the Bible — though not always, as in Alexander’s Feast — but in Handel’s treatment such stories could be just as intensely dramatic and emotionally riveting as what he had been writing for the opera stage. And oratorio had the advantage of being considered morally uplifting — and more edifying for audiences wary of the scandal-associated world of opera.

Israel in Egypt dates from this important transitional phase in Handel’s career. Following the miserable failure of his innovative opera Serse in April 1738, oratorio took center stage in his plans for the 1739 season. Saul, composed in the summer of 1738, became the first of his collaborations with the librettist Charles Jennens (best known for compiling Messiah’s libretto).

Until the discovery of an 1860 recording of “Au clair de la lune” in 2009, this haunting excerpt from Handel’s oratorio recorded in 1888 was the oldest known recorded human voice in existence.

For his next biblical oratorio, Israel in Egypt, Handel took a bold approach that was based on a libretto different from the standard model he had used in Saul. Israel in Egypt tells its story as a collage entirely composed of biblical texts (in the King James translation). Since this of course anticipates the method used for the later Messiah — the only other of Handel’s oratorios to use the Bible in this way — it has been conjectured that the uncredited libretto was indeed compiled by Jennens.

This method would present a problem for Handel’s London audiences when Messiah was introduced there in 1743. The criticism circulated that drawing on a sacred source for such a secular context — and oratorio was self-evidently a close relation to opera — was akin to blasphemy. But the subject matter of Israel in Egypt was entirely appropriate for the Lenten season, during which the work was premiered at the King’s Theatre in London, on April 4, 1739. As per his usual custom, the composer filled out the generous program with performances of organ concertos during the intervals.

A CHORUS-RICH ORATORIO — Originally titled Exodus, the genesis of Israel in Egypt, so to speak, is somewhat involved. Handel began with what became its final section (“Moses’ Song,” which draws from Exodus, chapter 15), composing it in the first two weeks of October 1738. He then turned to the more event-filled Part Two, title “The Exodus” (here, the libretto interweaves passages from Exodus and the Psalms). This took Handel less than a week to compose, and he completed the entire score by November.

But Handel also included an opening part, resulting in a neatly symmetrical tripartite oratorio in which the drama of the Exodus is framed by a lament-filled prelude and a kind of collective ode of joy at its conclusion. For Part One, Handel recycled music he had already composed for the funeral of Queen Caroline, consort of George II. Her death in November 1737 came as a personal loss to Handel, who had known her since his youth.

That earlier work, The Ways of Zion Do Mourn, is a dark, pathos-ridden funeral anthem that also draws from an assortment of Scripture and that Handel had considered incorporating into Saul. By altering just a few details of the text, the composer retrofitted Queen Caroline’s funeral anthem, titling it The Lamentation of the Israelites for the Death of Joseph.

In this form, the essentially pre-existing Part One provides the back story for the reversal of the Israelites’ fortunes in Egypt, which had resulted in their enslavement. Connections between the biblical archetype and contemporary political tangents crop up in the final part as well, in such numbers as “The Lord Is a Man of War.” This is in keeping, observes musicologist Christopher Hogwood, with “the belligerent political mood, as both Whigs and Tories, poets as well as politicians, pressed for a war with Spain.”

Along with a number of other self-borrowings, Israel in Egypt is notable for the amount of pilfering Handel makes from both old masters and some (now) rather obscure contemporaries. It has even been suggested that Handel intentionally drew on what was for him the equivalent of “early music” to give his retelling an archaic flavor. Still, there is no mistaking the signature of Handel himself both in the dramatic details and in the cumulative architecture that make this oratorio such a stirring musical experience.

Israel in Egypt did, however, receive a lackluster response at its premiere. Concerned with so many recent miscalculations regarding his audience, Handel radically changed the piece by cutting out the first part entirely. He seems to have decided that the collective lamentation of the first part was overkill, and Israel in Egypt was eventually published in a two-part version: “The Exodus” followed by “Moses’ Song,” which achieved spectacular renown in the chorus-loving 19th century. Mendelssohn, for example, found much inspiration here, conducting this oratorio frequently and helping to establish its popularity.

“One of the things that was off-putting to the audiences of Handel’s time was the high proportion of choruses in relation to the solo writing,” Gershon notes. “Messiah is the only other oratorio that comes close to the same number of choruses. And, like Messiah, Israel in Egypt has no real direct narrative. But what made it so hard for audiences in 1739 is precisely what makes it so compelling and attractive to audiences of the 21st century — the sense of a collective feeling and response that Handel creates with these extraordinary choruses.”

This evening marks the Master Chorale’s first-ever performance of the fuller, three-part original version of the work.

THE VISION OF KEVORK MOURAD — It’s interesting to note that the single most-famous highlight from Verdi’s breakthrough opera Nabucco is also a chorus: specifically, one that alludes to the situation of the Exodus from the perspective of the enslaved Israelites several centuries after Moses. The sense of historical patterns that recur, strata-like, has inspired the Syrian-Armenian artist Kevork Mourad as he developed his vision for this collaboration, his largest-scale project to date.

Kevork Mourad's creative process and how he combines art and music.

Based in New York since 2006, Mourad’s signature process involves a technique of painting in real time with ink he squeezes out of a bottle onto the page and then smears into patterns that coalesce into images. These are projected via Midi-controlled camera onto a large screen, as Mourad toggles between showing his live drawing and computer-animated manipulations.

“I love to keep the improvisational element,” Mourad explains. “I start by knowing the idea in my head of what I want to draw, but I don’t know from which corner I will start, for example. At first it may look random, but then the shapes become recognizable.” He incorporates the chorus by having them react at moments to the screen narrative; at others, the imagery is meant to appear “like an extension of their singing. It’s a way to give the audience eyes.”

Mourad became intrigued by the echoes between the catastrophic events that Handel depicts and their repetitions in more recent history. “This story is very familiar to me because of my Armenian background. My ancestors were forced to leave their homes 100 years ago and were welcomed by Syrians. And now this has happened to the Syrians: almost half the population has been forced to leave their homes. So there are three layers to this story for me.” His visual accompaniments to Handel’s music are intended “to create this space where the story is shifting in time. Sometimes it’s ancient, sometimes of today.”

Usually, Mourad works with his collaborators to shape the scenario, as in the acclaimed Home Within, which he created in partnership with the Syrian clarinetist Kinan Azmeh. Reflecting on the turmoil in Syria since revolution broke out, Home Within has toured widely. Israel in Egypt represents a different kind of challenge: “I’ve never used this kind of approach before, to enter into a massive work that has already been constructed. So I needed to figure out, how can I be part of it, how can I illustrate it from a different point of view? My paintings are like strata, like archeological layers of these different times throughout history. And it’s almost like the breath of Handel’s music is creating the piece. When the singers are singing, their breath is rising up to the screen and creating the piece. That is how I feel connected to Handel.”

THE MUSIC OF ISRAEL IN EGYPT — The vast majority of Parts One and Two is choral, with the exception of one aria and some brief recitatives, preceded by a brief, dark overture that establishes the grief-stricken mood of oppression from which Moses will have the mission to deliver his people. Handel’s treatment of his choral forces is remarkably varied. The gamut ranges from thrilling homophonic outbursts, grandly fugal edifices, and Venetian-style antiphony to echo effects from the double chorus, and, overall, imaginative word painting: again and again, Handel’s musical gestures enact or comment on what is being sung.

The orchestral palette is correspondingly large: along with the usual strings and continuo, Handel scores for woodwinds, trumpets, trombones, and timpani. Indeed, Gershon points out, this is one of the largest orchestras Handel ever used.

Throughout Israel in Egypt, the chorus serves multiple functions, playing the role of individual participants. In this sense, Handel further anticipates the unusual dramaturgy of Messiah: even Moses and the Pharaoh are referred to rather than actively characterized. The chorus by turns represents the omniscient biblical narrator and the Israelites, but their narrative distance from the events additionally carries a hint of the ancient Greek chorus.

Still, Handel never relinquishes the dramatic impulse that is at the core of his art. The sequence of plagues in Part Two presents a tour de force that takes the place of the lavish costumes, sets, and emotion-centered arias of opera seria. Handel gives us meandering anxiety in “They loathed to drink of the river,” the furious buzz of flies (“He spake the word”), powerful drum-and-brass punctuations for the hailstones, and disquieting harmonic dissolutions during the plague of darkness, culminating in the orchestral hammer blows that accompany the final plague against Egypt’s first-born. Handel even adds wry humor in the madly dotted rhythms of the alto aria describing the plague of frogs.

“I see the plagues as what humans do to destroy themselves,” says Mourad. “The idea of plague in our day is the destruction and catastrophe facing our own civilization, through wars and nonstop conflict. The story is so powerful and you can see it happening again through our own technology, our greed, our choices to destroy our own civilization and heritage. So while the singers are illustrating the plagues, I want to add something that is symbolic.”

Part Three centers around the crossing of the Red Sea and the Israelites’ rejoicing at being delivered from the pursuing Egyptians. A brief, harmonically wide-ranging instrumental introduction followed by a short chorus leads into the glorious statement of the oratorio’s central message, set for double chorus: “I will sing unto the Lord.” Handel recapitulates its jubilant theme at the conclusion.

The rest of Part Three recounts the sea crossing from different perspectives, interpolated with reflections on the power of divine intervention. Handel adds another kind of variety by incorporating a handful of arias and duets. There is likewise remarkable diversity in Handel’s depictions of “water music,” from the deceptively lulling phrases of “The depths have covered them” and the vivid use of registral contrasts in “And with the blast of Thy nostrils” to the undulating flow of the soprano’s aria “Thou didst blow with the wind” to describe this supernatural phenomenon.

“It’s easy to be dazzled by the pictorial aspect of Handel’s depiction of the various plagues,” observes Gershon. “But now when I approach Israel in Egypt, I look more toward Part Three and all the different ways that we can give thanks for this miracle — and for this restoration of homeland and identity. It is the Passover story, and it is so resonant because this is the story that has given hope to so many peoples over the centuries.”

Thomas May, program annotator for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, writes about the arts and blogs at memeteria.com.