- 2018-11-08

Theme and Variations: Praise and Unity

Read the program notes for our November 18 concert of Bach's Magnificat and the West Coast premiere of Reena Esmail's This Love Between Us: Prayers for Unity.

By Thomas May

“The lamps may be different, but the Light is the same: it comes from Beyond.” We encounter these words as set to Reena Esmail’s music in the last movement of This Love Between Us: Prayers for Unity. And in its eloquent concision, this text by the 13th century Persian poet and Sufi mystic JalÄl ad-DÄ«n Muhammad RÅ«mÄ« (otherwise known simply as Rumi) sheds light on the inspiration for Esmail’s oratorio. (Indeed, she initially planned to title it The Light Is the Same.)

“I’ve always wanted my music to connect people to one another,” she says, and in This Love Between Us, Esmail has composed a stunning mosaic that celebrates the unifying connections shared by a variety of Indian religious traditions — traditions that, in an increasingly fractured world, are cynically used to divide people.

Rumi

Division, partisanship, religious hatred: these became seeds for the Thirty Years’ War — that devastating stage rehearsal for Europe’s later world wars, the first of which was brought to its bitter end exactly a century ago last week. Not quite four decades had passed since the conclusion of the Thirty Years’ War when Johann Sebastian Bach was born.

Yet even in his most devoutly Christian compositions, created within a cultural and political context that was steadfastly Lutheran, Bach expressed a human universality that transcends parochial pieties. His art moves us to the core, regardless of our belief systems, communicating beyond dogma and the distance of centuries.

From a contemporary perspective, the differences between Catholicism and Lutheranism may seem relatively trivial, yet a mere generation before Bach they had led to mass casualties. In his setting of the Magnificat, which opens our program, Bach finds a common ground of his own between Protestant practice and the tradition passed down through the ages from Catholicism.

Johann Sebastian Bach

So how did this deeply devoted Lutheran come to set the Latin Magnificat, a text closely associated with the Virgin Mary and with Catholic worship tradition? Indeed, only on comparatively few occasions did Bach use Latin texts — the other major example being, of course, the Mass in B minor, which also may have involved an attempt at ecumenical “outreach” of a sort (as an overture to possible employment by the Catholic court in Dresden). In Leipzig — and such matters varied from one municipality to the next in Protestant lands during this era — Luther’s German translation of the Magnificat was sung during regular Vespers. However, the Latin text familiar from its usage by the Roman Catholic Church was retained for such special feasts as Christmas.

Visitation by Franz Anton Maulbertsch

Bach’s inaugural year as music director of the churches in Leipzig, in 1723, began too late for him to have a chance to write something fresh for the Easter or Pentecost services, so the first opportunity that presented itself to pull out all the stops for a major feast was at Christmastime. Later, the composer would grow disillusioned with his Leipzig bosses and with aspects of the post that shackled him creatively, but in 1723 he wanted nothing more than to outdo even his own high standards.

According to the scholar Christoph Wolff, Bach envisioned providing an ambitious and expanded Magnificat setting for his first Leipzig Christmas to give his new employers — and, of course, the congregation — a dazzling impression of the role he intended that music would play under his tenure: no more dust-off-the-stale-scores of liturgical music, no more uninspired routine.

This was in the context of Bach’s plan to write entire annual cycles that would require a new cantata from his own pen for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical calendar. His Magnificat of 1723, in the key of E-flat major, incorporates other Christmas-related numbers throughout that link it specifically to this time of high festivity. It was the single most ambitious work he had composed to date since starting the post in Leipzig.

Between 1732 and 1735, Bach revisited his original Magnificat score and pruned away the extra numbers so that it could be adapted to any feast day Vespers service. He additionally transposed the score to D major — a key with connotations of festivity — and changed some of the instrumentation (for example, flutes instead of recorders). This later score (BWV 243 in the catalogue) calls for solo vocal quintet, five-part choir as well, and an orchestra of flutes, oboes (plus oboe d’amore), trumpets, timpani, violins, viola, and continuo. It is the standard repertory version.

The spirit of expansiveness that guided Bach in his 1723 setting can be seen in the homage he pays to international styles and to musical traditions from the past — all with the goal of establishing a sense of continuity with the present moment in Leipzig.

Leipzig

Also known as the Canticle or Song of Mary, the Magnificat is a Latin translation of the Greek text from the first chapter of the Gospel of Luke, where it represents a proclamation of praise by the pregnant Mary during her visitation to her cousin Elizabeth. Far from innocently platitudinous in its praise, the Magnificat reads like the manifesto of a social justice advocate. (How exactly do adherents of the “prosperity gospel” explain this particular biblical text?)

Bach divides the prayer into 12 sections, but even the choral movements that call for a full display of performing forces are concise. Such concision powerfully enhances the contrasts between sections and the swiftly moving imagery of Mary’s exultant prayer. Through moment-by-moment word painting and musical symbolism, Bach engages us deeply, unleashing the power of the five-part chorus in the opening section and bringing it back at key moments (such as the “Omnes generationes” and “Fecit potentiam”). Certain emotions triggered by the text activate rhythmic ideas, such as the animated energy in the soprano aria “Et exultavit.” Melodic shapes and instrumental colors enrich the Magnificat’s stream of images overall. In “Quia respexit,” the oboe d’amore mixes its distinctive timbre with the first soprano in a more restrained mood, while the alto’s “Esurientes implevit” is luxuriant, almost operatic. But just at the moment when the 1% get their just due and are “sent away empty,” Bach eliminates the charming flutes.

Another fascinating example of his strategic contrasts is seen in the juxtaposition of familiar local tradition with a musical symbol of European-wide learning: Bach weaves a chorale tune from the German Magnificat (given to the pair of oboes, which his listeners would have recognized immediately) into the beautiful vocal trio “Suscepit Israel,” which he follows with a contrapuntal chorus that links the fugue with the Law represented by Old Testament prophecy.

At the end of the final chorus (a setting of the “Gloria Patri,” which serves as a kind of cadential prayer to the Magnificat text), Bach brings back the festive music with which he had launched the work: resplendent trumpets and timpani with concerto-like treatment of the vocal lines (playing the role of other instruments in this context). Mary’s song of praise and joy has no beginning or end but echoes timelessly, like the moments of deep intuition conveyed by the canonical texts that Reena Esmail has chosen for her oratorio.

A member of the Indian diaspora born and based in Los Angeles, Esmail draws on her background negotiating different cultural identities to explore the spaces and coherences between them through her music. That experience similarly fuels the composer’s sense of artistic purpose of wanting to connect people from different backgrounds and contexts.

Composer Reena Esmail. Photo by Rachel Garcia.

Esmail explains that the Muslim-Catholic-Indian-Kenyan-Pakistani background she gained from her parents has made her all the more sensitive to the need for such connection. “I’ve often felt that my choice to be a Western musician separated me from my cultural heritage. That is why so much of my work now exists between the traditions of Western and Indian classical music.”

Along with earning degrees in composition from Juilliard and Yale, Esmail spent a transformative year in India as a Fulbright Scholar, where she focused on Hindustani musical traditions with the sitarist Gaurav Mazumdar as her mentor. She currently serves as one of two co-composers-in-residence with Street Symphony in downtown Los Angeles (whose founder and artistic director, Vijay Gupta, recently was made a MacArthur Fellow). In September, Gupta premiered Esmail’s Darshan for solo violin, another work that responds to models by Bach.

Other projects this season by the increasingly sought-after Esmail, who was named Musical America’s “New Artist of the Month” in August 2017, include last week’s performance of her work Teen Murti by the Chicago Sinfonietta as part of an orchestral Diwali celebration and, this spring, major world premieres of works commissioned by the Richmond Symphony and Chorus, and by cellist Joshua Roman.

This Love Between Us: Prayers for Unity reimagines the Western format of the oratorio, whose origins are closely associated with the Christian tradition, as a context for exploring deeper connections between the seven major religious traditions found in India. It also responds to the positive message of Bach’s Magnificat with a contemporary sensibility of enlightenment.

The connection between both works resulted from the circumstances of a co-commission that Esmail received in 2016 from Juilliard 415 (a program focused on early music practice) and Yale’s Schola Cantorum. She was asked to write a new choral work that would share the program with Bach’s setting. “As a composer, it’s pretty rare to get that kind of commission — which includes composing for so many instruments you haven’t written for before [i.e., for period instruments]. It even gave me a chance to use three natural trumpets!” Esmail says.

This Love Between Us was premiered in New York in 2017 and then presented on a tour to India (in New Delhi, Mumbai, and Chennai). Tonight’s West Coast premiere represents a sort of homecoming: not only is the composer a native Angeleno, but she points out that Paul Salamunovich was the choir director of the church she attended growing up (St. Charles Borromeo). “That was the first choir I ever heard, and I’m sure that the first professional choir concert I experienced was the Los Angeles Master Chorale.”

Preparing this performance has been an intricate process, starting back in the summer, Esmail explains. On one level, that process sounds like a metaphor for the connections she seeks out in the oratorio itself. “People from two different cultures and different musical trainings have to figure out new methods and systems of working together. The process is different every time, and that’s the beauty of it.”

The scoring requires implementing this ideal of working together. It combines a Baroque orchestra (pairs of flutes and oboes/oboes d’amore, a bassoon, three trumpets, timpani, and strings) and Western choir with solo sitar and tabla. The sitarist Rajib Karmakar is originally from India, while the tabla player Robin Sukhadia is an Indian-American who grew up in the United States.

Robin Sukhadia, Reena Esmail, and Rajib Karmakar.

For the parts that call for improvisation using the Indian instruments, Esmail had to find ways of mediating with the precisely-written-out notation used by the Western ensemble. “In a way I feel as if I’m a translator between the leaders of different countries, trying to figure out what value system each person has and how to convey that in a way that is respectful and makes them want to engage with each other. With a cross cultural collaboration like this, when you want to create a space that allows each person to speak their own language and still be understood, it takes so much more time than the length of a Western orchestral rehearsal.”

Esmail culled texts from the seven religious traditions that show how each deals with “the topic of unity, of brotherhood, of being kind to one another.” Her family is connected to two of these seven religions (Islam and Christianity), and her training encompasses the study of Hindustani music (which belongs to neither of those religions), she remarks.

But even with this richly cross-cultural background, locating the most fitting such excerpts posed intense challenges. She worked with almost two dozen colleagues to do this and to help with the technical aspects — pronunciation, diction, meaning — as well, since her method of setting the texts involves another kind of union, in that each movement simultaneously presents both the original language of the text and its English version. (The one exception is in the third movement, where Esmail uses a Malayalam translation of the original Greek from a New Testament passage, thus incorporating the language spoken in the southwestern state of Kerala, where Christianity first appeared in India.)

Each of the seven movements of This Love Between Us contains what the composer describes as “a unique combination of Indian and Western classical styles.” Overall, the musical language spans a continuum from Western classical to Hindustani, with varying mixtures between. Thus, Esmail combines Western choral textures with passages for solo singers who vocalize in an Indian style in different ways throughout the oratorio.

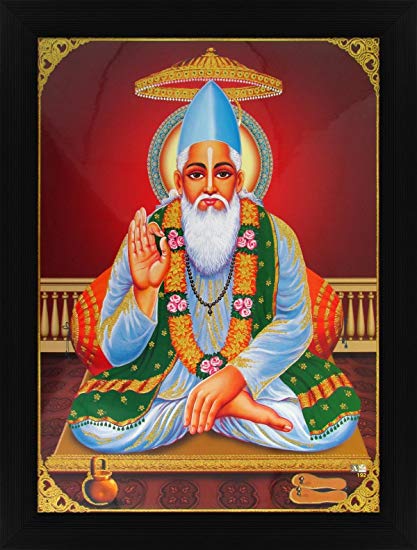

The first movement (Buddhism: text in Sanskrit, from the Dhammapada) establishes these two horizons from the start, with powerful tutti gestures from the whole ensemble and chorus, later giving the spotlight to the sitar and tabla. There are references to the style of Sanskrit chanting, though no quotations from actual chant. The second movement (Sikhism: original text in Gurmukhi from the Guru Granth Sahib) introduces a beautiful grace note figure, chromatically inflected, which quotes a Sikh devotional song recommended by one of the team of colleagues the composer consulted. Esmail observes that this figure is “not necessarily a marker of Sikhism.” Rather, she was inspired by this particular song from the Sikh tradition and became fascinated by how such a tiny gesture (the grace note) “can give the whole piece a completely different flavor — like a pinch of a spice.”

Guru Granth Sahib

In the third movement (Christianity: original text “reverse translated” from New Testament Greek to Malayalam, from Letter to the Romans), Esmail makes explicit reference to Bach’s Magnificat by using the three trumpets that were at her disposal. This is where the oratorio, drawing on Baroque choral style, is most fully anchored in the Western tradition. Its counterpart comes in the fully Hindustani style of the fourth movement (Zoroastrianism: Pahlavi, an earlier form of Persian and a language that is not even spoken anymore, from the Pahlavi Rivayat). Scored for solo baritone solo, this is the only movement that is structured in a completely Hindustani classical form: specifically, as a vilambit bandish, a composition at a very slow tempo, which would serve as the anchor point for likely 30–45 minutes of improvisation in a Hindustani concert.

The fifth moment (Hinduism: Hindi, combining texts from the Isa Upanishad and from the 15th-century Indian mystic poet Kabir) is a love duet for soprano and tenor in basic song form (ABA). A point to note about the simultaneous language treatment here: when the love duet returns in the second “A” section, the voices switch so that the tenor sings in Hindi, the soprano in English. The text from Kabir, whose legacy is claimed by both Hindus and Muslims, gave Esmail the source for her title This Love Between Us.

Kabir

In the sixth movement (Jainism: Ardhamagadhi Prakrit, from the Acharanga Sutra), a fiery musical expression predominates, despite the Jains’ association with radical peacefulness. “I wanted to include a counterpoint to the other parts of the oratorio that are often so warm and soft, with a text setting out things that are forbidden” — restrictions intended to pave the way to harmonious living.

The seventh movement (Islam: Persian, the poetry of Rumi, including “affirming phrases from other religions”), which concludes the work, shares the poet’s message that liberation will come if you “concentrate on the essence/concentrate on the light.” Here and in the Hinduism movement, Esmail sets the words of “poets who write through the lens of their religion” — with Rumi representing the Islamic perspective, since it would be blasphemous to set a text from the Koran to music. This movement contains longer passages of choral a cappella writing, changing keys constantly. The sitar and tabla meanwhile improvise freely in a Hindustani raga (i.e., a pre-established melodic framework) known as Raag Vachaspati during sections that are settled in a single tonal center.

Esmail worked on the oratorio in 2016 during a period she says felt very dark because of the outcome of U.S. presidential election, and she recalls that her belief in the necessity of art was reinforced, above all its role as “a way to rehabilitate our society.” This Love Between Us culminates with “Amen” like phases, prayer cadences from these varied traditions, overlapping in layers of hope and harmony.

Thomas May, program annotator for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, writes about the arts and blogs at memeteria.com.