- 2018-06-05

Questions and Answers: A New Context for The Brahms Requiem

Discover how works by Caroline Shaw (pictured) and David Lang will pose questions answered by the Brahms Requiem at our season finale concerts June 9 & 10.

by Thomas May

At first glance, the choice of a Requiem as the central work for the season’s closing program may seem a bit … somber. But Johannes Brahms’s choral masterpiece — which also happens to be his longest and largest score — is no ordinary Requiem. For one thing, the deeply personal approach that led Brahms to craft his own, non-traditional sequence of texts means that this is an anti-doctrinaire Requiem, with no interest in salvation or damnation but in the work of memory on the part of the living.

And for anyone who loves the art of choral singing, the Brahms Requiem commands a particularly sacred status, so to speak. As a compositional achievement, it was a longstanding preoccupation of the legendary choral conductor Robert Shaw, a transformative figure for the choral scene in the United States. Shaw planned to record a new English version he had lovingly prepared at the very end of his life but died in January 1999, only a few weeks before that project could be realized.

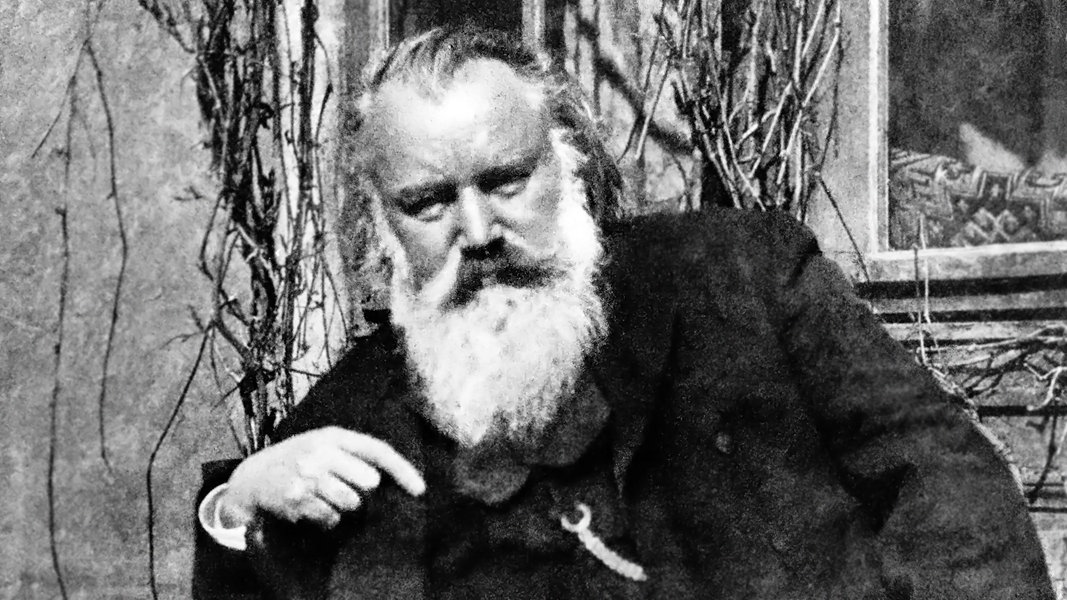

Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897)

Grant Gershon, the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s Kiki & David Gindler Artistic Director, decided to program a pair of short choral works by living American composers as a kind of prelude, suggesting a contemporary context in which we will then hear Brahms’s magnificent score. In contrast to the choral and symphonic forces of the latter, the pieces by Caroline Shaw and David Lang are both a cappella. “Both are open-ended as well, asking questions,” Gershon says. “This performance of the Brahms is the answer to the questions that the first two pieces will raise.”

The winner of the Pulitzer Prize in music in 2013 for her a cappella Partita for 8 Voices, Caroline Shaw is also a singer in the Grammy-winning ensemble Roomful of Teeth and a violinist. She has gained cultural visibility beyond the new classical and choral spheres for her role in the Mozart in the Jungle series and for a collaboration with the rapper Kanye West. Fly Away I dates from 2012 and was written for the International Orange Chorale of San Francisco. Framed by an intoned solo tenor line, the piece begins with an improvisatory, intimate sequence of solo voices singing the phrase “I’ll fly away,” followed by the altos’ repeated chanting (“I went the way”) — to be sung “almost like speaking, very naturally, like one of those late-night conversations.” When it reaches full force, Shaw instructs the ensemble to create a sound “like velvet concrete.” Shaw makes striking and effective use of the juxtaposition between spare, monotone lines and harmonic abundance.

Caroline Shaw – ”Passacaglia” from Partita for 8 Voices

David Lang, another Pulitzer Prize winner (in 2008 for the little match girl passion, part of the Master Chorale’s repertoire), composed where you go for chamber choir in 2015 to mark the 75th anniversary of the Tanglewood Music Center.

where you go “is a rewriting of what I remember as my favorite part of the biblical Book of Ruth, the famous lines where Ruth tells [her mother-in-law] Naomi that she will stay with her forever,” writes the composer. “I say ‘what I remember’ because in my memory the book is a beautiful statement of love, friendship, and devotion, from one person to another. I always forget that the book is mostly a series of legal arguments, about how someone claims land, or an inheritance, or a wife, or a family. Ruth’s simple desire to follow her heart sets in motion an examination of a complicated chain of interlocking obligations and overlapping responsibilities. That pretty much describes my piece as well.” Gershon values the “emotional and bittersweet” qualities of where you go, a piece which “seems to ask the same questions that the Brahms Requiem asks, just in a different language.”

David Lang – our hearts are glowing from “The National Anthems” recorded by the Los Angeles Master Chorale

A VERY HUMAN REQUIEM — “Of all the major composers in the history of music, Brahms was perhaps the only one to have distinguished himself as a choral conductor,” observes the musicologist/conductor Leon Botstein. Brahms’s choral conducting went hand-in-hand with his emerging reputation as a composer. Few premieres in his career proved to be as significant as that of the Requiem.

In fact, the world premiere is a somewhat complicated story. An initial unveiling of the first three movements in Vienna in 1867 fared poorly, but the bulk of the work made a powerful impression when Brahms conducted it at the Cathedral in Bremen on Good Friday in 1868. (One movement was not heard at that time: the fifth, featuring solo soprano. The complete, seven-movement Requiem premiered in February 1869 in Leipzig.)

The unorthodox approach taken by Brahms confused even some of his fervent supporters. His avoidance of conventional references to Christianity troubled contemporaries like Karl Reinthaler, the Lutheran organist at Bremen Cathedral, who remarked: “For the Christian mind, however, there is lacking the point on which everything turns, namely, the redeeming death of Jesus.”

Brahms’s title Ein deutsches Requiem (“A German Requiem”) points to the original nature of the work in comparison with the longstanding tradition of musical settings of the Mass for the Dead. Even such freethinkers as Giuseppe Verdi contributed to the Latin Requiem tradition known from Roman Catholic liturgy. (Verdi’s came a little later, in 1874.) But Brahms, born into the Protestant tradition and given to an undogmatic humanism in lieu of traditional faith, replaced this model with a newfangled design of his own. “German” in the title refers to the language of the texts Brahms culled for his libretto. Tellingly, he also declared that he may just as well call the work “A human Requiem.”

Martin Luther’s German translation of the Bible served as Brahms’s source, from which he wove an eclectic tapestry using excerpts from the Psalms, Isaiah, the Book of Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, and the New Testament. As a “Requiem,” Brahms clearly has in mind a connection to the ancient liturgical tradition of a Christian Mass in memory of a deceased person. At the same time, not a single movement of Ein deutsches Requiem corresponds exactly to the lineup we find in the Requiem settings by Mozart, Verdi, or Fauré, for example. Take the Dies irae, with its theatrical depiction of Judgment Day (constituting a massive portion of the Verdi Requiem): this is conspicuously absent from Brahms’s Requiem.

Not that Brahms’s strategy of his selecting his own texts was entirely unprecedented. Handel’s Messiah is the best-known example of a similar method of piecing together various scriptural selections to trace the narrative of the nativity, passion, and resurrection of Jesus. Other composers of the Renaissance and Baroque — eras of intense interest to Brahms as a student of music history — also anticipated this method of using selected texts to create a musical memorial. Famous examples included the Passions of J.S. Bach and the Musikalische Exequien of Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672). Los Angeles Master Chorale audiences are familiar with a contemporary manifestation of this “collage” approach in the boldly conceived librettos of Peter Sellars for John Adams’s El Niño and The Gospel According to the Other Mary.

In his Requiem, Brahms shifts the focus away from pleading for the redemption of the deceased, away from dreading “the undiscovere’d country, from whose bourn/No traveler returns.” His music is geared instead toward consolation of the living. After all, young Brahms found himself in desperate need of consolation when his beloved mentor and friend Robert Schumann, suffered his terrible demise while in an asylum and eventually died in 1856.

The death of the composer’s mother in 1865 was another impetus. In her memory, he wrote what became the fifth movement, which contains some of the score’s most beautiful music and the line “I will comfort you as a mother would.” (Incidentally, the Brahms authority Michael Musgrave thinks that the usual story — that the composer wrote movement five as a kind of postscript, later interpolating it into the score — is inaccurate. Musgrave posits that Brahms withheld it from the Bremen premiere because he needed to see the audience’s reaction before allowing such a private confession to become public.)

Thomas May, program annotator for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, writes about the arts and blogs at memeteria.com.

Caroline Shaw photo by Kait Moreno.