- 2017-09-15

Behold, How Good: Choral Masterworks by Bernstein and Orff

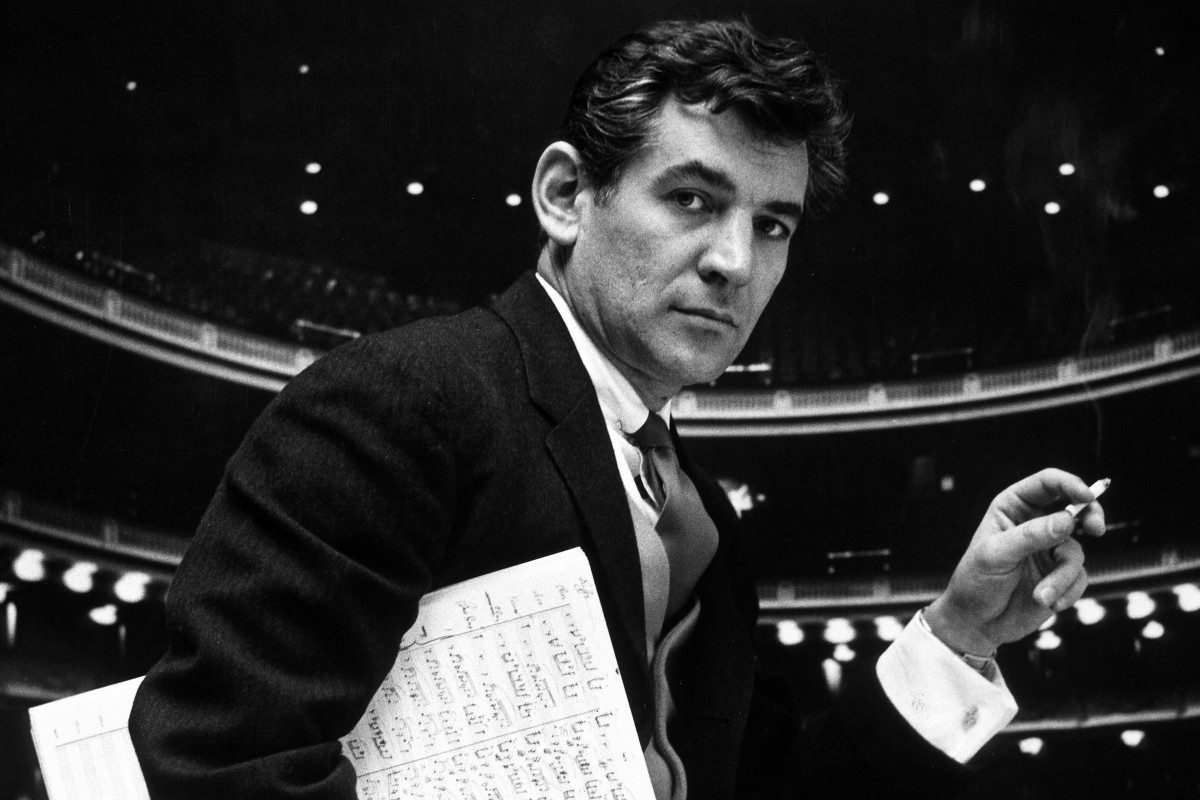

"This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before." Leonard Bernstein’s timeless statement — made in response to the assassination of President Kennedy, and shortly before he received a request to compose what would become Chichester Psalms — reminds us that we need him more than ever.

“This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.” Leonard Bernstein’s timeless statement — made in response to the assassination of President Kennedy, and shortly before he received a request to compose what would become Chichester Psalms — reminds us that we need him more than ever.

As it happens, next year marks the centenary of the great man’s birth, and the music world will devote two seasons to celebrating what Bernstein achieved and what he stood for. “Bernstein at 100,” as the hashtag goes, officially kicked off on Friday at the Kennedy Center, the venue founded to carry forward JFK’s vision for the role of the arts in an advanced nation. In 1971, for the Kennedy Center’s grand opening, Bernstein composed the music theater work Mass (which promises to be one of the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s highlights with the LA Philharmonic in February).

Chichester Psalms is an ideal work to launch the Master Chorale’s new season. “It makes a wonderful complement to Mass and allows us to present two of Leonard Bernstein’s greatest choral works in the same season,” says Artistic Director Grant Gershon. He notes as well that this setting of sacred texts, which remains among Bernstein’s most beloved compositions, still has much to tell us today about the vitality and uplifting power of choral music.

In this sense, Chichester Psalms pairs effectively with another modern choral classic, Carmina Burana. Bernstein and Carl Orff shared a democratic passion for communicating the power of music. “Another common thread is that both pieces have this big, open-hearted, larger-than-life quality that is all embracing,” notes Gershon.

Crisis in Music, Crisis in Faith

But the exuberance we encounter in Chichester Psalms was hard-won. Bernstein likened what he referred to as “the crisis in music” — basically, the loss of belief in a shared musical language — with a “crisis in faith” that had been exacerbated by the horrors of the 20th century. Chichester Psalms exemplifies one of the ways he found to respond to both crises at once — if only for a brief time. Bernstein came back to these issues again and again, above all in Mass, arguably his masterpiece.

Leonard Bernstein

The request mentioned above, which Bernstein received in December 1963, came from the Dean of the Cathedral of Chichester in Sussex. “Many of us would be very delighted if there was a hint of West Side Story about the music,” the Dean added. Bernstein was then in the middle of his tenure leading the New York Philharmonic but took a sabbatical during which he wrote the requested new piece, intended for a festival of combined English cathedral choirs to take place in the summer of 1965. The proposal was at first for a setting of just one Psalm. Bernstein decided instead to fashion a suite of three movements (setting texts from a total of six Psalms).

Using the working title Psalms of Youth, he set the texts in the original Hebrew — which language, it’s interesting to note, had also been incorporated into Bernstein’s recently completed Third Symphony (“Kaddish”), a profoundly somber work dedicated to the memory of the slain JFK. In contrast to the darkness of the Kaddish Symphony, Bernstein intentionally underscored the rejuvenating element of Chichester Psalms (the title he ultimately chose, concerned that “Psalms of Youth” might be mistaken as a piece for young performers). “The soprano and alto parts are written with boys’ voices in mind,” he wrote in the preface to the score, while the solo in the middle movement should be sung “by a boy or a countertenor” (the vocal representation of a young David) — although Bernstein allowed for women’s voices to be used instead.

The sabbatical found Bernstein trying to write various pieces in a style that he, as a serious composer, was “supposed” to follow: in a distinctly experimental, “post-tonal” idiom. But he felt it to be inauthentic: “After about six months of work I threw it all away. It just wasn’t my music; it wasn’t honest,” Bernstein later recalled. “The end result was the Chichester Psalms which is the most accessible, B-flat majorish tonal piece I’ve ever written.” Chichester Psalms might also be seen to reconcile the conflict between “serious” and “popular” styles that Bernstein felt so acutely. You’ll immediately note the overt, jazz-infused references to that unique energy of Broadway (especially in the second movement, when the chorus bursts in: “Why do the nations rage?”).

Each of the three movements is progressively longer. The first is compact and alludes to one of Bernstein’s heroes, Mahler (from the Eighth Symphony, another choral work addressing issues of faith). A thematic idea Bernstein introduces here recurs throughout as a unifying device. The hint of menace in that choral outburst of the second movement is brushed aside by the serene return of the soloist’s melody — the voice of faith shows a way beyond violence.

Yet darker currents come back in the instrumental prelude to the third movement. With a nod to Berg’s Violin Concerto, Bernstein evokes the reassuring ethos of a Bach-like chorale and then concludes Chichester Psalms with a plea for universal peace.

What Goes Up Must Come Down

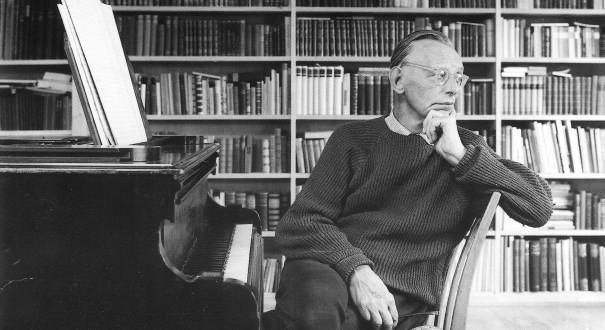

It’s surprising to realize that the long-lived Carl Orff, who once fought in the First World War for his native Germany, died in 1982, only eight years before Bernstein. “Orff took nine-tenths of the style [in Carmina Burana] from Stravinsky’s Les Noces and the other tenth from Israeli horas,” Bernstein once quipped — though, it might be added, the Carmina Burana sound has been identified by several critics as one among the vast range of allusions to be found in Bernstein’s Mass.

Both composers shared a conviction in the virtues of music education and in the possibility of tapping into what they believed was an innate ability for people to enjoy music — as universal as the ability to communicate in language. Orff developed a method for teaching children that became widely influential.

Carmina Burana emerged against this background — and against Orff’s own problems with atonality while not wanting to reject the advances of Modernism wholesale. This is where the Stravinsky connection comes into play. Both Stravinsky’s choral works from the 1920s (especially Les Noces, the celebration of wedding festivities the Master Chorale performed last season) and the “primitivist” breakthrough ballets he wrote before the First World War for the Ballets Russes influence the sound world of this score.

Carl Orff

Orff additionally shared with Stravinsky a fascination with reimagining the ancient world through modern eyes. Ancient Greek theater presented a model, in his view, in which all the performing arts had been amalgamated into a unified whole. This, coupled with his excited discovery of the medieval collection of poems he used as the texts for Carmina Burana, might make Orff sound like just another Wagnerian, but his music here is oriented toward the anti-Romantic spareness and stylization of Stravinsky.

Carmina Burana was conceived as a “scenic cantata” and was premiered in a staged version at Frankfurt Opera (in 1937). Orff had something more ambitious in mind than the work that has become so familiar from being excerpted in film scores and commercials: an impressive panoply of visuals, costumes, lighting, and dance. Indeed, he envisioned Carmina Burana as just one part of a triptych and went on to write two related cantatas on classical themes (Catulli Carmina and Trionfo di Afrodite), all of which were to comprise an evening-length trilogy (known collectively as Trionfi).

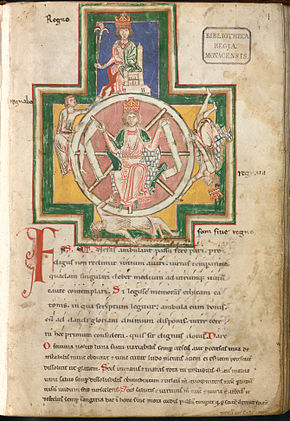

The idea for Carmina Burana was triggered by a chance discovery in a rare bookstore, where Orff came across an old edition of a miscellany of 254 medieval poems titled Carmina Burana. The poems had been found in a manuscript at a Benedictine monastery in the composer’s native Bavaria. (“Burana” is the Latin version of the German place-name for Beuern, the town where the monastery was located, and “Carmina” is simply the Latin plural for songs or poems.)

The manuscript was discovered in the early 19th century, around the time of reawakened interest in fairy tales and folk poetry (think Des Knaben Wunderhorn and the Grimm Brothers). The Carmina — mostly composed in Latin but with some medieval vernacular mixed in (Middle High German and Old Provençal) — had lain hidden in a monastery, but the subject matter of many of these poems is decidedly profane and satirical, praising the pleasures of Eros and other worldly pursuits.

The poems are thought to be the work of Goliards — the wandering hippies of the Middle Ages who took a break from their university studies and amused themselves with literary games. Their outlook was at a far remove from that of the troubadours Wagner cherished, who idealized the cult of romantic love. At first, the frank eroticism (including musical depictions of orgasm) did not sit well with the Nazi cultural arbiters in power at the time of the work’s premiere, but — an ongoing problem for Orff’s reputation — Carmina Burana did become popular during the Third Reich. (Orff was no Nazi, but the issue of his career during this period remains hotly debated.)

Carmina Burana manuscript

Orff’s full title emphasizes the profane and even pagan nature of the material: Carmina Burana: Cantiones profanae cantoribus et choris cantandae comitantibus instrumentis atque imaginibus magicis (“Carmina Burana: Secular Songs for Singers and Choruses To Be Sung Together with Instruments and Magical Images”). Note there as well the centrality of the singers, whom the ensemble is there to accompany. His score seeks out the pristine, magical power of music itself — “enchant” means to enrapture, to cast a spell through singing.

Orff organized the cantata into 25 numbers framed by the image of ancient Roman goddess Fortuna as the “Empress of the World.” Fortune is the implacable force contrasted with the anarchic urges of desire illustrated in the cantata’s various narrative threads and mini-stories. We encounter a triptych of the sensual delights found in nature (“In the Springtime” and “On the Meadow” — numbers 3-10), in social life (“In the Tavern” — numbers 11-14), and in the amorous but bittersweet awakening of courtship (“Court of Love” — numbers 15-23).

The image of Fortuna as a turning wheel is mirrored by the cycle of the seasons, the unpredictable ups and downs of gambling, reversals of social roles, even — most graphically — a swan being turned on the spit. The most enchanting section of the score depicts the emotional highs and lows of sexual passion (the final vignette, “Blanziflor and Helena” — number 24).

In musical terms, Orff reinforces the imagery of desire’s repetitive patterns through his stripped-down use of striking rhythmic mottos and almost ritualistic refrains, as well as sharp contrasts in dynamics. As in Stravinsky’s version of Modernism, old-fashioned thematic development is jettisoned in favor of repetitive formulas and continual metrical variety. Using an expanded percussion section, Orff tends to build with large blocks of sound to reinforce the mostly choral vocal parts. It’s also possible to hear aspects of this score as anticipations of Minimalism.

Orff evokes a pre-Christian, pagan sensibility through clever word painting that, also as in Stravinsky, manages to sound simultaneously archaic and modern. The score alternates between moments of high-spirited exuberance and serene introspection — but pleasure and pain are, after all, revealed to be opposites of the same coin.

By Thomas May

Thomas May, program annotator for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, writes about the arts and blogs at memeteria.com.