- 2019-04-24

Lights, Camera, Sing! A Season Finale From Stage and Screen

Read Thomas May's program notes on the opera choruses and film scores featured in our final concerts of the season, Great Opera & Film Choruses, May 4 & 5 in Walt Disney Concert Hall, conducted by Grant Gershon, Kiki & David Gindler Artistic Director.

By Thomas May

When opera began to emerge in the late 16th century, it relied heavily on Renaissance interpretations of ancient theater (no matter how speculative and indeed mistaken we now know those to have been). So it makes sense that choruses significantly affected the very conception of the genre: as in the model from ancient Greek tragedy, the chorus provided commentary and even engaged in dialogue with the protagonists; they were also crucial in creating atmosphere. (Think of the “infernal spirits” versus the nymphs and shepherds in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo.)

And opera in turn has played an important role in the evolution of the cinema. Both art forms use the chorus for a vast range of expressive purposes, and the potential seems inexhaustible. Grand choruses account for some of the most exciting moments in opera being written today, while another renaissance might almost said to be under way in the ingenious ways that today’s film composers are incorporating choral music into their scores — as we will experience on this season finale program.

“Composers are finding new ways to use voice and choral music in film — not just the standard oooo’s and aaaa’s that supplement the sound of the orchestra, but more individual ways of using the voice, even to the point of creating language,” remarks Grant Gershon, Kiki & David Gindler Artistic Director of the Master Chorale. In selecting these concerts' program, he turned to pieces “that have a very strong profile — for both the opera and film selections. I wanted to focus on music that paints a scene as well as music that helps to tell a story. Everything has a strong sonic profile — whether it’s the goofiness of the minions singing in Despicable Me or the super-creepy atmosphere of the music for Us.”

.jpg)

Grant Gershon, Kiki & David Gindler Artistic Director of the Master Chorale and Resident Conductor of LA Opera.

The opera selections turned out to be a good deal easier to select, given Gershon’s lifelong familiarity with the repertoire and the enormous amount of potential material to choose from. “For me the revelation has been with the film scores.” Rather than a mere “nostalgia trip” reveling in film hits from yesteryear, he made it a criterion to spotlight more recent scores as well as the diversity of composers at work in the field — a field in which the Master Chorale singers are actively involved. “The contribution of Edie Lehmann Boddicker as the artistic consultant on the film music programming cannot be under-valued,” declares Gershon. “We simply would not have a program that is so relevant, diverse, and that epitomizes the excellence of this field without her.”

Following is a brief guide to each of our program’s selections:

Where have all the dragons gone? Inspired by Cressida Cowell’s book series, the How to Train Your Dragon franchise imagines a more enchanted era when dragons intermingled with humans — and could even become their companions. The Hidden World is the third installment in the computer-animated action fantasy HTTYD trilogy and was released just this year. In his Suite from The Hidden World, Los Angeles-based English composer John Powell (b. 1963) uses epic vocals to conjure the utopia sought by Toothless and the other dragons with the help of his special friend, Viking Hiccup Horrendous Haddock III — a place free from the predations of Grimmel the Grisly.

John Powell

Our first opera selection comes from one of the most violent works in the repertoire. Ruggero Leoncavallo’s (1857–1919) brief verismo masterpiece I Pagliacci, which premiered in 1892, has not lost its power to shock with its tale of murderous jealousy. But the Bell Chorus helps establish the calm before the storm. As the people in a small town wait for the evening comedy to be performed by a traveling theater troupe, the church bells signal Vespers while the younger villagers sing of the evening’s promise of “light and love.”

Ruggero Leoncavallo

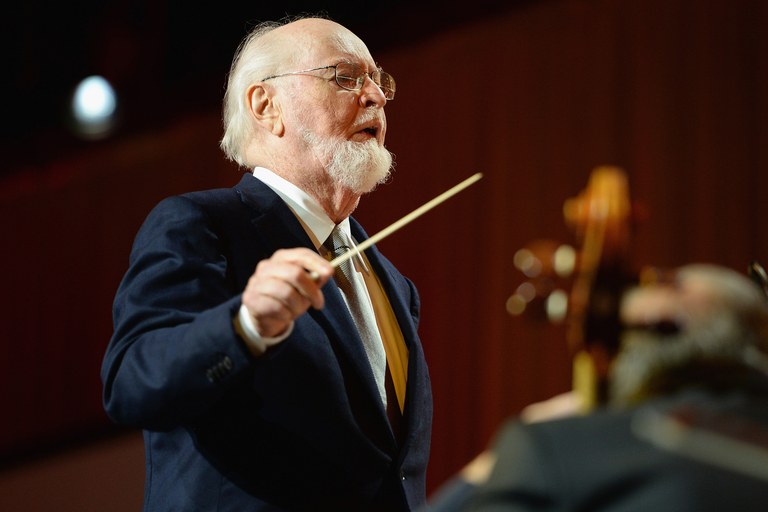

In his teens, John Williams (b. 1932) moved with his family to Los Angeles, where he got to work with masters of the film music trade like Bernard Herrmann and Franz Waxman. He has gone on to shape what audiences over the past four decades expect not only from film scores but even from “classical music” itself. Williams’s very first score for Star Wars in 1977 made movie and music history, and he subsequently composed the scores for all seven other installments in the Star Wars space opera film franchise — including the most recently made, The Last Jedi, which was released in December 2017. He has announced that the ninth (to be released at the end of the year) will be his final Star Wars score. Williams is celebrated for his epic use of brilliantly orchestrated themes, but the chorus also gets to shine in this epic about an emerging generation of resistance heroes — in fact, the Master Chorale itself sings on the original soundtrack.

John Williams

When Oscar-winning composer Michael Giacchino (b. 1967) agreed to write the music for J. J. Abrams's 2009 film Star Trek — the 11th installment in that uber-popular franchise, which introduced a new cast for the rebooted film series — he faced a lot of pressure in wanting to satisfy the enormous fan base of a show Giacchino himself had grown up loving. The epic results, played by a 107-piece orchestra and sung by a chorus of 40, did not disappoint. Giacchino wrote his own themes while also paying homage to the unforgettable original theme by Alexander Courage (which in turn — by coincidence? — echoes a moment from the first movement of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony).

Michael Giacchino

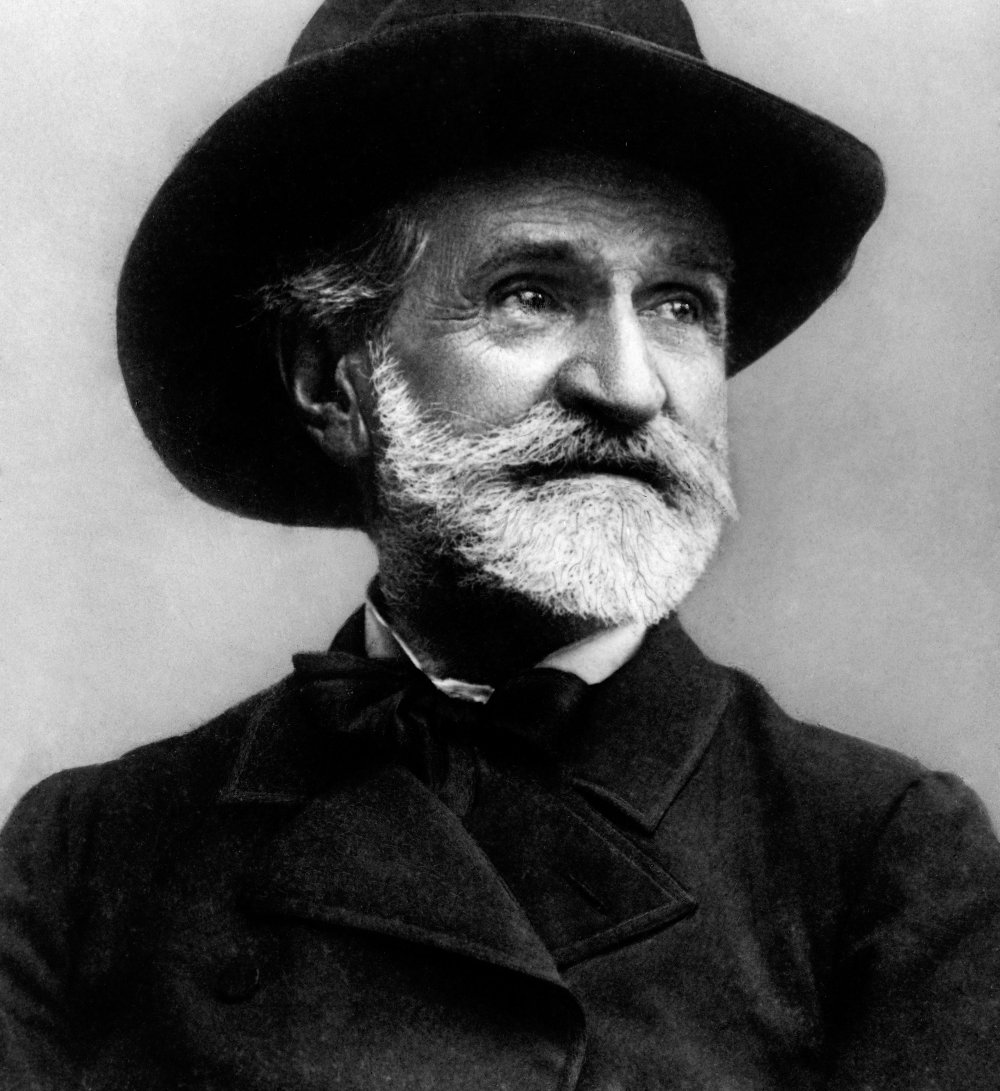

Nabucco marked a turning point for young Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901), who nearly abandoned his career before agreeing to try one more time by taking on a libretto based on the period of the ancient Israelites’ captivity in Babylon. The chorus “Va, pensiero” is the best-known moment in a work in which the chorus in its own right serves as one of the main characters — here representing the collective memory of the enslaved Israelites longing for the homeland from which they were torn away. Nabucco’s triumph in 1842 set Verdi’s career into high gear, and it was sung during the composer’s funeral procession nearly 60 years later.

Guiseppe Verdi

The first Latina composer invited to join the Music Branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Germaine Franco (b. 1962) is a trailblazer in the industry. She started out as a drummer and came to film composing via writing music for the stage, finding an especially helpful mentor in John Powell. Franco also became the first female composer to join the Dreamworks studio team. The 2018 comedy film TAG, which marked the directorial debut of Jeff Tomsic, is loosely based on a real-life story about a group of adult men who continue playing a particularly aggressive version of the childhood game of tag. “Dove’s Loophole” comes from the climactic scene.

Germaine Franco

Much as opera has its storied partnerships (Mozart and Da Ponte, John Adams and Peter Sellars), the chemistry between composers and directors is responsible for some of the most remarkable film scores. Danny Elfman (b. 1953) wrote the music for Tim Burton’s 1985 feature directorial debut (Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure), the first of a remarkable legacy of collaborations that has included Edward Scissorhands, the Batman films, The Nightmare Before Christmas, and many more — including Burton’s 2010 re-telling of the Lewis Carroll classic in his darkly fantastical, unique style. Elfman, a native Angeleno, writes magically for the chorus to create Alice in Wonderland’s soundscape, centering his score around themes evoking the brave heroine.

.jpg)

Danny Elfman

For all the revolutionary attitude that drove him — impacting not only opera but ideas about theater and the arts in general — Richard Wagner (1813–1883) drew significant inspiration from the grand opera practices he later denounced. His early opera Tannhäuser — the first work he completed (1843) in Dresden after scoring his initial success there — is a case in point. Wagner adapted a medieval legend of redemption through love, dramatizing the plight of the troubadour Tannhäuser. An outsider rejected from his society after seeking extreme experience through sin, he must atone for his transgression by making a pilgrimage to Rome but is told by the Pope himself that forgiveness would be possible only if his wooden staff were to sprout fresh leaves. In this final scene from the opera, a group of Pilgrims is seen returning from Rome, singing one of Wagner’s most memorable, long-limbed melodies and announcing that the miracle has in fact happened: Tannhäuser has been saved through the prayers of his beloved Elisabeth.

Richard Wagner

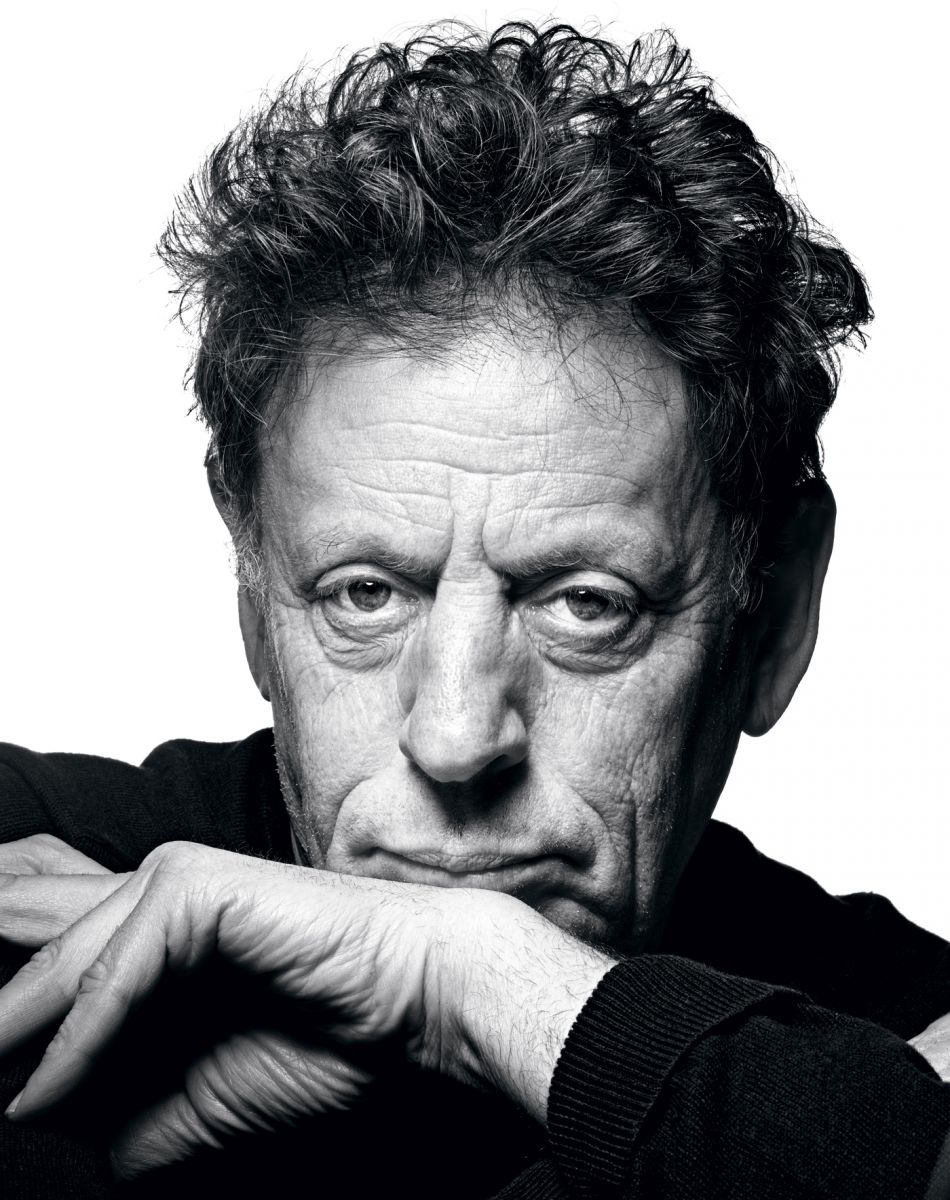

Philip Glass’s (b. 1937) significance has long reached far beyond the world of contemporary classical music. His prolific activity writing music for film, which has given wider circulation to his signature style, is a natural development for a composer who thrives on the process of collaboration. Opera has been similarly crucial to his work. In fact, Glass helped pave the way toward the renaissance in contemporary opera that continues to unfold with the three “portrait operas” that launched his career as an opera composer. The third of these, Akhnaten (1983), explores the spiritual revolution triggered by the 14th-century BCE Pharaoh who introduced the principle of monotheism before his dramatic downfall. His rise-and-fall story is foreshadowed by the funereal solemnities for his father Amenhotep III in the opening scene (sung in the ancient original language of the Egyptian Book of the Dead). The ritualistic drumming sets the stage for a musical pageant representing the old order that Akhnaten will challenge after he ascends the throne.

Philip Glass

Hailing originally from Phoenix and growing up in rural South Dakota, Michael Abels (b. 1962) was a prodigy who began composing as a child. He later studied at the USC Thornton School of Music as well as the California Institute of the Arts. Along with acclaimed orchestral works such as the much-performed Global Warming (1991) and his 2000 opera Homies & Popz (written for LA Opera), Abels has become widely known for his collaborations with actor-director Jordan Peele. Abels was invited to write the music for Peele’s first film, Get Out, the enormously successful, genre-defying indie release from 2017 that reflects on racism in allegedly “post-racial” contemporary America using a horrific twist on the 1967 Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? as its premise. Get Out revolves around an ill-fated visit by Chris, its young black protagonist, to meet the parents of his white girlfriend. Abels incorporates the Swahili phrase “Sikiliza Kwa Wahenga” (“listen to your ancestors”) into the main title as a subliminal warning for Chris to be vigilant about his disturbing surroundings.

The 2017 Pixar fantasy film Coco tells a touching story of the living meeting their dead ancestors and the power of music. With lyrics by Adrian Molina, “Proud Corazón” composed by Germaine Franco and sung at the end of the film sums up the young hero Miguel’s adventures on the Mexican tradition of the Día de los Muertos.

Danny Elfman had many fantastic images to work with when he began writing the music to Edward Scissorhands. Tim Burton’s 1990 classic dark fantasy involves the outcast title character, an artificially created human left “unfinished” when his inventor suddenly dies. The lonely Edward’s love interest is Kim, the daughter of the saleswoman who takes him in. Edward (played by Johnny Depp) uses his scissor-bladed hands to carve an ice sculpture in her image at Christmastime, inspiring the ethereal scene of Kim’s "Ice Dance.”

Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) found his initial inspiration to create his beloved opera about the clash of cultures when he encountered David Belasco’s one-act play Madame Butterfly as part of a double bill while visiting London for a Tosca production. (The composer later made Belasco’s The Girl of the Golden West into an opera as well.) Puccini’s lack of English didn’t hamper the overwhelming effect the story had on him — especially Belasco’s wordless depiction of the young Japanese bride’s all-night vigil as she waits for her American husband (who has abandoned her), assuming he will return. Puccini translated this theatrical effect (which made an innovative use of lighting) into the Humming Chorus (Coro a bocca chiusa, literally, “chorus [sung] with the mouth closed”), for sopranos and tenors. It takes place during the transition to what Cio-Cio San awaits as a new day of hope — though this tragically turns out to be an illusion.

Giacomo Puccini

Grammy-winning composer and musician Heitor Teixeira Pereira (b. 1960) made his entrée into creating music for films by writing songs (for As Good As It Gets). “Clouds Lifted” is the closing song off the 2018 film Smallfoot, one of the Brazil-born composer’s more recent efforts. Directed by Karey Kirkpatrick, the computer-animated Smallfoot cleverly flips the script of the “abominable snowman.” A society of Himalayan Yetis decides to ostracize one of their community, Migo, when he challenges them with his discovery of a “smallfoot” after he encounters a plane crash survivor who proves that the existence of humans isn’t merely a myth.

Heitor Pereira

Smallfoot is based on a children’s book (unpublished) by screenwriter/animator Sergio Pablos, who also hatched the idea for the Despicable Me franchise — a computer-animated film series about super-villain Felonious Gru. Despicable Me 3 recounts Gru’s travails after being recruited as an anti-villain agent — and his problems with the franchise’s signature small yellow Minions, who want him to continue his career of villainy. Pereira has collaborated with the rapper/songwriter Pharrell Williams on the three installments of Despicable Me to date (2010, 2013, and 2017). As part of a talent competition in the film, the Minions sing “Papa Mama Loca Pipa,” replacing the lyrics of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “Major-General Song” (the famous patter song from The Pirates of Penzance) with nonsense syllables. It soon became a YouTube sensation.

We conclude not only with music from the highest-grossing film of the year (as of this writing) but another set of firsts in this evening’s parade of breakthroughs. Captain Marvel, a saga involving the interstellar Kree-Skull conflict became the first Marvel Studios film to be headlined by a female superhero (Brie Larson). And its composer, Pinar Toprak (b. 1980), broke through the glass ceiling by becoming the first woman to score a Marvel Cinematic Universe film. After studying classical composition and jazz and getting a start as part of Hans Zimmer’s studio, the Turkish-American composer has built her career writing music for video games, TV series, and a variety of film genres. Toprak immersed herself in the sounds of 1990s action movie scores, but it was while taking a walk that she came up with the unforgettable Carol Danvers (aka Captain Marvel) theme. “She’s one of the most powerful beings in the universe, but she’s also very human … strong yet sensitive,” remarked Toprak in a recent interview with Variety. “I wanted to hear the humanity instilled in the hero.”

Pinar Toprak

Thomas May, program annotator for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, writes about the arts and blogs at memeteria.com.