- 2018-11-26

Sweet Singing in the Choir: An English Cathedral Christmas in Los Angeles

Judith Weir, Gustav Holst, Thomas Tallis, Cecilia McDowall, and Henry VIII are some of the composers you will find on our eclectic English Cathedral Christmas program conducted by Grant Gershon December 2.

By Thomas May

It’s that time of the year again, when the endless loop of predictable carols in commercial settings all too easily sours the intended holiday cheer. More’s the pity, since the international wealth of Christmas-related music from traditional and modern sources seems inexhaustible.

Even if you limit yourself to the framework of the English cathedral choral tradition, a cornucopia of new discoveries awaits. Grant Gershon, Kiki & David Gindler Artistic Director of the Master Chorale, was determined to avoid a greatest hits potpourri when designing this evening’s program, so he cast his net wide. He remarks that about three-quarters of the selections he decided to include had been previously unknown even to him.

Gershon's guiding idea was to explore the English cathedral tradition of music related to Advent in survey fashion. But other than restrict the program to a chronological order, the conductor prioritized what would offer the most compelling flow musically and emotionally — treating this source material, in other words, not unlike how a composer organizes and juxtaposes the mass of ideas that go into a larger piece.

“I wanted to include as many composers as I could within the parameters of the theme,” says Gershon. At the same time, while most of this evening’s selections are specifically related to the Advent theme, he opened it up to include some exceptions that illustrate the essence of the Christmas spirit at different times of the year as well: a spirit of “coming together to celebrate and enjoy a good time.”

Because of the way English choral traditions have unfolded historically, the selections gravitate toward the Tudor period (with a little pre-Tudor material) or pieces from the 20th century and today, with not much between. This survey makes no claim to completeness (Purcell is noticeably absent), and Gershon includes some outliers (the Norwegian Ola Gjeilo’s treatment of a classic English carol and a Christina Rossetti poem set by the American Robert A. Harris).

In terms of choral singing tradition, what is it that makes this music so recognizably English? “There is a certain warmth and sonorousness that goes all the way back to the late Middle Ages in the English choral tradition,” says Gershon. “They were among the first composers who really fell in love with and fully exploited triadic harmony, in contrast to the more austere sense of harmony from medieval times and chant tradition. That carries through to the present day in the aesthetic of an extremely sophisticated, blended sound.”

HENRY VIII: PASTYME WITH GOOD COMPANY

Though voted to the top of the list for “worst monarch in history” by the British Historical Writers Association — as a “self-indulgent wife murderer and tyrant” — Henry VIII did have some redeeming qualities: including a remarkable musical talent. He is believed to have composed at least two settings of the Mass. About onethird of the “Henry VIII Songbook” (c. 1518) in the British Museum is attributed to Henry’s pen. Pastyme with good company dates from happier days early in his reign — Henry was a few days from his 18th birthday when he was crowned king in 1509 — and its tune proved memorable enough to spread well beyond the privileged confines of court.

THOMAS WEELKES: HOSANNA TO THE SON OF DAVID

Emerging out of the end of the Tudor era, organist and composer Thomas Weelkes made his name as one of the great madrigalists in this era of English music. He became associated with Chichester Cathedral, though his alcoholism led to public scandal and career setbacks. Hosanna to the Son of David, dating from the early 17th century, illustrates the brilliance of Weelkes’ music in the so-called “full-anthem” style, i.e., using the full resources of the choir, here divided into a resonant six-part texture (framed by two soprano and two bass lines). The text is taken from the Gospels of Luke and Matthew.

PETER WARLOCK: BETHLEHEM DOWN

Peter Warlock was the pseudonym used by the colorful Anglo-Welsh composer and critic Philip Haseltine (1894-1930), a friend of Frederick Delius and passionate researcher of English folk music. Drinking also plays a role in the backstory to the choral anthem Bethlehem Down. Warlock and his journalist friend Bruce Blunt (author of the text) teamed up to write it on Christmas Eve in 1927 as their entry in a carol contest, using the proceeds to finance a bout of drinking. The style of this carol-anthem hearkens back to Tudor models, though Warlock’s homophonic choral writing and unusual harmonies make for a distinctly original sonority, both timeless and modern.

THOMAS TALLIS: O NATA LUX DE LUMINE

The remarkably long-lived Thomas Tallis was a creative force across the reigns of four monarchs (Henry VIII, Edward VI, “Bloody” Mary, and Elizabeth I) — which means he had to accommodate the dizzying pendulum swings between Catholic and Protestant political-aesthetic regimes and the corresponding expectations for church music. The five-part motet O nata lux de lumine (O light born of light) is a jewel of homophonic choral writing, its dazzling flashes of unexpected harmonies flavoring the word setting. This piece likely comes from late in his career. It was published as part of an Elizabethan anthology of Latin motets that appeared in 1575 as “Cantiones Sacrae”.

HERBERT HOWELLS: A SPOTLESS ROSE

The English composer, organist, and teacher Herbert Howells drew on Tudor models as well as such older contemporaries as Elgar and Vaughan Williams to formulate a distinctive style, making substantial contributions to the repertoire of Anglican church music. A Spotless Rose dates from 1919, early in Howells’ long career, and was written as the middle panel in a set of three carol-anthems. The text comes from an anonymous 14th-century poem celebrating the birth of Jesus from “Mary, purest Maid” — a miracle unfolding “in a cold, cold winter's night.” Howells includes a radiant solo in the second verse, ending the piece with an A minor-to-E major cadence of which fellow composer Patrick Hadley proclaimed: “I should like, when my time comes, to pass away with that magical cadence.”

THOMAS TALLIS: ALLELUYA

This ethereal piece comes from early in Tallis’ career, during the reign of Henry VIII, in whose personal Chapel Royal the composer would come to serve. Associated with the so-called “Lady Mass” (Mass in honor of Mary), this setting of the Alleluia may date from the 1530s. The scholar John Harley observes that here the composer’s “main interest was in the sound of treble voices soaring, as though pictorially, above the voices beneath.”

JUDITH WEIR: I LOVE ALL BEAUTEOUS THINGS

Appointed Master of The Queen’s Music in 2014, Judith Weir writes music that has been deeply influenced by various folk traditions. She composed the four-part I Love All Beauteous Things (with organ accompaniment) on a commission from St Paul’s Cathedral in London to mark Queen Elizabeth II’s 90th birthday in 2016. The text is from a poem by Robert Bridges (1844 – 1930), who was poet laureate in 1926, the year of the Queen’s birth. Weir admires Bridges as “an outstanding humanitarian and writer” and also wrote a song cycle, The Voice of Desire, to his poetry. The composer remarks: “This short, fast-tempo setting aims to emulate the swift, fleet-footed rhyme and meter of the two-verse poem, with its unobtrusive but telling reference to ‘man in his hasty days.’”

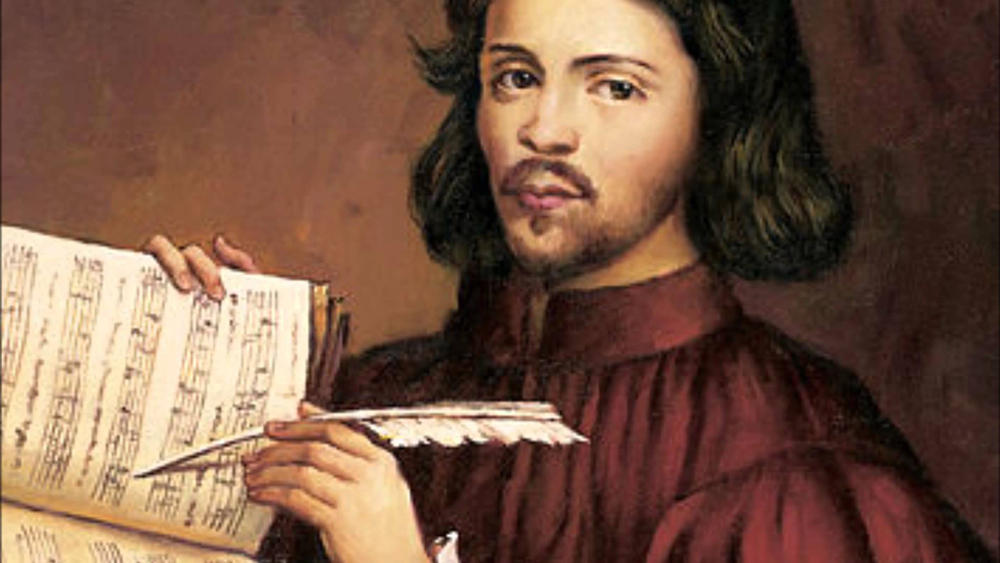

WILLIAM BYRD: SING JOYFULLY

One of the preeminent architects of the English choral style, William Byrd was a Catholic recusant in Reformation England (that is, conspicuously absent from legally mandated Anglican worship). Yet he won the favor of Queen Elizabeth and served as a member of the Chapel Royal in her court and, with his mentor Thomas Tallis, was even granted the exclusive right to publish music. The gloriously polyphonic, six-part anthem Sing Joyfully, which circulated widely, represents his writing for a Protestant audience early in the 17th century: Byrd here sets verses from Psalm 81 in its version from the Geneva Bible — familiar to Shakespeare — which preceded the King James translation.

CECILIA MCDOWALL: BEFORE THE PALING OF THE STARS

Winner of the 2014 British Composer Award for Choral Music, the London-born Cecilia McDowall is a much sought-after choral composer. It’s easy to hear why in such eloquent pieces as Before the paling of the stars, which sets an 1859 text by Christina Rossetti (and later published in the early 20th-century anthology “Christmas Carols: Old & New”). McDowall composed her setting on a commission from the Choir of the Royal Memorial Chapel, Sandhurst, in 2012. Each voice in the four-part piece enters in descending registral order (SATB), accompanied by organ.

JOHN TAVENER: THE LAMB

“I think the Sacred can happen anytime, in any place, in any genre,” John Tavener once remarked. “What is most important is that we remain totally transparent, totally vulnerable, and totally open.” The mystically inclined Tavener passed through a period of avant-garde experimentation before deciding to focus on “the essence of music” (his term), aiming for a mindful simplicity unburdened by the distractions of the ego. The Lamb was written in an afternoon in 1982 for the composer’s nephew. Tavener restricted himself to a melody of seven notes to set the famous poem from William Blake’s “Songs Of Innocence”. The Lamb symbolizes Jesus, who will be sacrificed, and Tavener’s setting has become associated with Christmas.

WILLIAM BYRD: THIS DAY CHRIST WAS BORN

Byrd’s Anglican anthem This Day Christ Was Born, for six parts (SSAATB), sets an unrhyming English version of the Latin Magnificat antiphon “Hodie Christus natus est” (sung at Christmas Day Vespers). It comes from late in the composer’s career and was published in his final publication in 1611, the title of which is: “Psalmes, Songs, and Sonnets: some solemne, other joyfull, framed to the life of the Words: Fit for Voyces or Viols of 3. 4. 5. and 6. Parts. Composed by William Byrd, one of the Gent. of his Majesties honourable Chappell”.

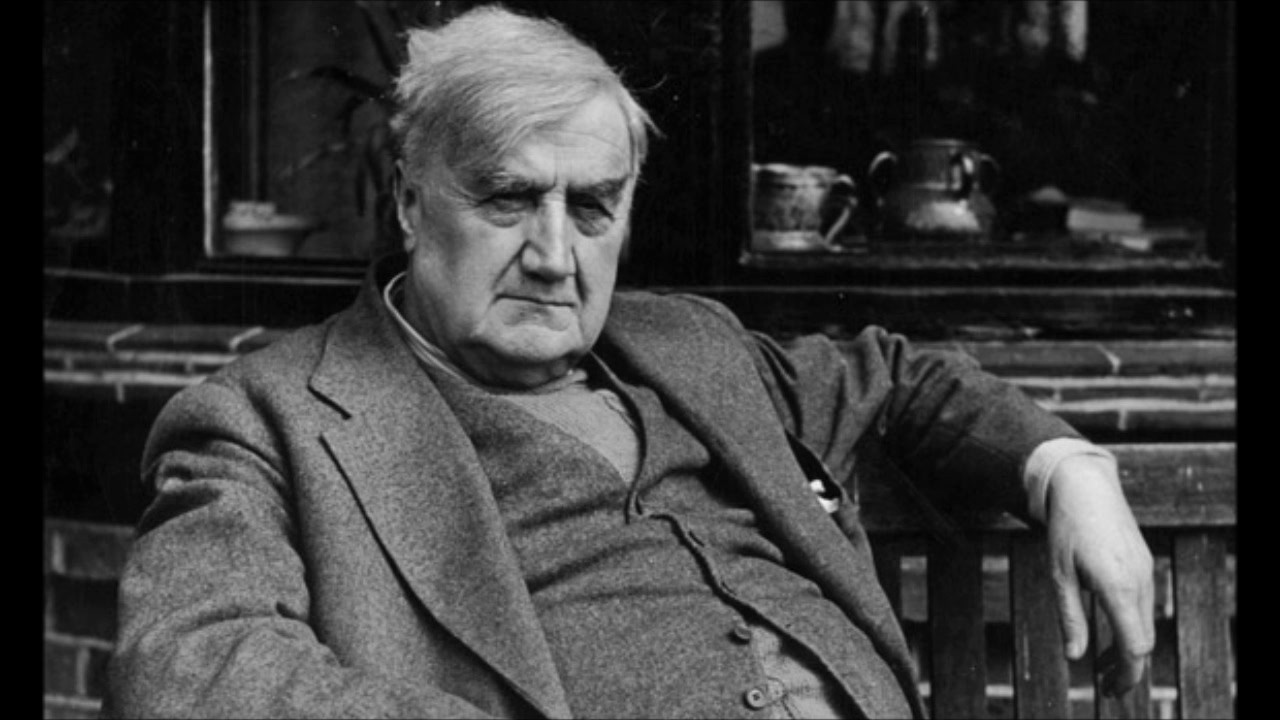

RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: WASSAIL SONG

The legacy of the great Tudor composers (Tallis, Byrd, and company), along with English folk tradition, deeply influenced Vaughan Williams. He became an avid collector of folk songs and was tasked with compiling “The English Hymnal” in 1906. Dating from 1913, his arrangement of the Wassail Song tune was included in his Five English Folk Songs collection. Here, we return to the “drink theme” that happened to comprise a minor thread in our program. The act of holiday wassailing (from an old Anglo-Saxon cheer to “good health”) refers to the exchange of drinks of festive spiced ale for caroling. Various wassail tunes became associated, respectively, with specific regions of England. This one comes from Gloucestershire.

BENJAMIN BRITTEN: THE SYCAMORE TREE

Another significant cultivator of English folk traditions, Benjamin Britten here sets the traditional English carol text I Saw Three Ships for four-part mixed choir. It originated in 1930 while the composer was at the Royal College of Music, though he revised it for publication decades later. Recall that Britten was still just a teenager when he composed this piece, and the originality and energy of its voice seem all the more astonishing.

HERBERT HOWELLS: SING LULLABY

The poet and broadcaster Frederick William Harvey (1888 - 1957), known as “the Laureate of Gloucestershire,” was a friend of Herbert Howells. He set Harvey’s lyric Sing Lullaby as a four-part Christmas anthem in 1920, making it the third of his carol anthems (following A Spotless Rose). Howells’s musical concept foregrounds the contrast between the gentleness of the falling snow, which frames the middle stanza, with the foreshadowing of the crown of thorns.

ROBERT A. HARRIS: LOVE CAME DOWN AT CHRISTMAS

Internationally active as a conductor and choir clinician, Robert A. Harris was a longtime professor of conducting and director of choir organizations at the Northwestern University Bienen School of Music (where he remains as an emeritus professor). He has also served on the Choral Panel of the National Endowment for the Arts. Harris’s Love Came Down at Christmas is a four-part choral setting he wrote in Christina Rossetti’s poem of the same name. His graceful rhythmic articulation of the main melody brings to mind the origin of so many carol tunes in the physicality of the dance.

CECILIA MCDOWALL: NOW MAY WE SINGEN

Commissioned by Concord Singers and premiered in 2007, this piece sets a 15th-century carol text (in English, with short Latin passages). McDowall explains that she chose to set it “in a linear style, spare in texture, to resonate with the words.” Sopranos and altos first sing the joyful melody before sharing it with the rest of the choir, enhanced by the harmonies of the other voices, which at times resemble tolling bells.

OLA GJEILO: THE HOLLY AND THE IVY

The Norwegian born, New York-based Ola Gjeilo, lists an eclectic blend of inspirations that includes “the improvisational art of film composer Thomas Newman, jazz legends Keith Jarrett and Pat Metheny, glass artist Dale Chihuly, and architect Frank Gehry.” The Holly and the Ivy is one of a set of seven arrangements of classic Christmas carols from 2012, that were commissioned for Nova Chamber Choir’s “To Whom We Sing” Christmas CD. The richly symbolic text transforms originally pagan symbols into Christian ones.

RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: THE FIRST NOWELL

Along with the earlier “English Hymnal”, Vaughan Williams edited the “Oxford Book of Carols” in 1928, returning to this topic during the Second World War, when the British Council requested a set of carol arrangements to be used for Royal Forces stationed in Iceland. The composer thus had to restrict himself to unaccompanied male voices. Oxford University press published nine of these in 1942 as Nine Carols for Male Voices. In a letter to the pacifist composer Michael Tippett, Vaughan Williams described his belief that artists must involve themselves “to preserve the world from destruction.” The carols project was an example of “using one’s craft for a definite useful purpose.”

GUSTAV HOLST: CHRISTMAS DAY

A close friend of Vaughan Williams (who dedicated his great Mass in G minor to him), Gustav Holst similarly cast his creative attention back to the rich history of the English carol tradition to arrange a medley of three beloved tunes for Christmas Day, which he subtitled “choral fantasy on old carols.” The three in question are Good Christian Men, Rejoice, God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen, and Come, Ye Lofty, Come, Ye Lowly (also known as the Old Breton Melody), which is presented in tandem with The First Nowell added in. Holst had his students in mind when he prepared his medley for chorus and organ, which Gershon singles this out as one of his personal favorites.

WILLIAM MATHIAS: A BABE IS BORN

The Welsh composer and pianist William Mathias is probably best known outside the British Isles for having written the anthem for the wedding of the Prince of Wales and the late Lady Diana Spencer in 1981. His version of A Babe Is Born, which originated as a Latin hymn in the 14th or 15th century, was commissioned by the Cardiff Polyphonic Choir in association with the Welsh Arts Council in 1971. Mathias’s new setting has become an especially admired example of the potential for carol traditions to be recharged with contemporary sonorities and inspiration.

Thomas May, program annotator for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, writes about the arts and blogs at memeteria.com.